Rehabilitating refugees, reconstructing Bangladesh

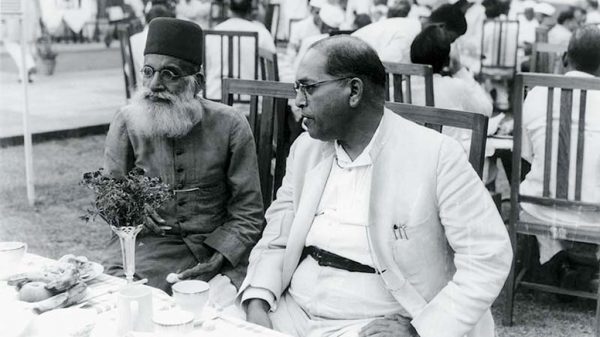

Dr. Atiur Rahman:

Bangladesh was born with virtually nothing in its coffers. The nine-month war of liberation caused not only human deaths but also massive destruction of all but a few of its physical infrastructures. The railways, bridges, roads, ferries, telecommunications, mills and factories, and ports were destroyed in the war. Much of this destruction took place just following the massive cyclone of 1970, which wiped out thousands of people and homes.

The Pakistani government not only destroyed the economy but also took away all the ships, airplanes, managers, administrators, engineers and technicians that could be useful in rehabilitating and reconstructing Bangladesh. Most of the West Pakistani entrepreneurs, administrators, engineers and technicians left Bangladesh when they were sure that Bangladesh was going to win the war.

And one must also remember that Bangladesh was already lagging behind West Pakistan due to the one-eyed policy of West Pakistani elites, which treated East Pakistan as a neo-colony to transfer resources from. As a result, Bangladesh emerged from the war of independence in 1971 having the highest rural population density in the world, with an annual population growth of nearly three per cent, and fertility rate of around six per eligible couple, with chronic malnutrition and extreme poverty among most of the population. Dislocation of ten million refugees who had fled to India had also returned to the country waiting for quick rehabilitation. There was not even a dollar in the foreign exchange reserve of the central bank, which too had to be rebuilt.

In addition, the newly emerged Bangladesh was facing myriads of challenges including restoration of law-and-order, handing over of the arms possessed by freedom fighters and others, negotiating the return of the Indian armed forces who fought for Bangladesh, settling the issues of prisoners of war and the collaborators of the occupying Pakistani forces, and managing the sky-high expectations of the youths who experienced the trauma of the liberation war.

These challenges had to be faced by the political leadership without much administrative experience. So, the homecoming of Bangabandhu, the lighthouse of freedom for the Bengalis, was both crucial and timely. Despite all the ordeals he endured in the Pakistan jail, he remained composed, and began to project hope and optimism to his struggling people as soon as he was freed.

In my previous piece, I have discussed the homecoming episode of Sheikh Mujib. On his way home he had to briefly touch London and Delhi. While in London, he attended a press conference where one of the journalists asked him ‘what would you do going back to Bangladesh which is devastated?’ As a visionary leader, Bangabandhu replied full of self-confidence, ‘We will rise again if I have my land and people’ (Hussain, S. A., ‘Bangabandhu’s Development Philosophy: Reconstruction and Growth with Equity’, Bangabandhu: The People’s Hero, External Publicity Wing, MOFA, 2020). That statement provided clear evidence of how determined he was to rebuild war-ravaged Bangladesh. While in Delhi, he pronounced that Bangladesh would be a land of peace, progress and prosperity. He repeated these words in Dhaka as well, where about a million freedom-loving people gathered to welcome their beloved leader. He did not spoil a moment after his return and plunged into the rehabilitation and reconstruction of Bangladesh’s economy and society.

It was not an easy job as the per-capita income in 1970-71 declined by about 22 per cent from that of 1969-70. Agriculture suffered deeply during the war. The rice production in 1972 was 15 per cent lower than that of 1969-70 (Planning Commission, Government of Bangladesh, The First Five Year Plan, 1973-78, p. 26). The money supply increased by 83 per cent during the same period, fueling inflation (ibid). The sudden jump in the oil price did not help, increasing the inflation of imports. It was, therefore, not surprising that large segments of the urban population were struggling to recover and regain confidence. As different sections of people had divergent expectations about independence, it became tough for the government to mitigate the conflicts of interest (Hossain, K. Bangladesh: Quest for Freedom and Justice, University Press Limited, 2019 fourth impression, p. 123).

There was an acute shortage of food grains following the national and international natural calamities. Yet, Bangabandhu was full of optimism and declared on the first anniversary of independence, “We will turn this war-ravaged country into a golden one. In the Bengal of the future, mothers will smile and children will play. It will be a society free of exploitation. Start the movement of development in the fields and farms and the factories. We can surely rebuild the country through hard work. Let us work together so that the Golden Bengal shines again” (Rahman, A. ‘Bangabandhu’s Thought on Development: Focus on Industrialization’, The Financial Express, 2018).

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was determined to overcome these challenges by establishing an equitable society. He was in favour of a homegrown socialist economy. He took some prudent and pragmatic initiatives to ensure agricultural growth, which was the backbone of the economy. Some of these initiatives were: rebuilding the war-ravaged agricultural infrastructure, ensuring the supply of agricultural equipment on an emergency basis, either free of cost or at concessional rates, ensuring an adequate supply of seeds, canceling 1.0 million certificate cases for loan default against farmers filed during the Pakistan period, fixing minimum fair prices for agro-products, ration facilities for poor and marginal farmers, etc. These initiatives built the foundation towards fulfilling the dream of sustainable and inclusive development in Bangladesh.

To materialise the dream of an exploitation-free society where resources would not be channeled in the hands of the bourgeoisie, Bangabandhu opted for a planned economy with intellectual inputs from a strong planning commission led by Professor Dr. Nurul Islam. Bangabandhu decided to launch the Plan early as the government felt ‘the urgent need to provide a sense of direction and determine the order of priorities within the framework of which coherent and consistent policies and programs could be formulated’ (ibid., ‘Foreword’). Even before the Plan was formally launched, the government began a massive nationalisation program in alignment with the pledges of an exploitation-free society. The government stepped in to nationalise the Jute, Sugar and Textile industries, banks (excluding branches of foreign banks), and the insurance companies (excluding the foreign insurance companies). A major portion of inland and coastal shipping, the national airlines, and the national shipping organisation were formally brought under state regulation. Properties of all absentee owners with assets valued at Taka 1.59 million or more, in addition to major portions of foreign trade, were nationalised (S.A Karim, Sheikh Mujib Triumph and Tragedy, The University Press Limited, 2005, p. 276-277). That did not mean Bangabandhu was against the private sector. He believed in balanced development. He, therefore, raised the private investment ceiling to Taka 30 million from Taka 2.5 million in the budget for 1974-75. Besides public and private sectors, he was also keen on developing the cooperative sector. He did all this to achieve the economic freedom he had pledged to the nation.

On February 7, 1972, at a reception program hosted by Kolkata Press Club, Sheikh Mujib said, “Bangladesh is committed to build an exploitation-free society. Independence becomes meaningless without economic emancipation. We cannot let the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. None in Bangladesh shall die of hunger; all will live in happiness and prosperity”. Mujib put in great efforts to take pro-poor development policies just after the liberation war. The government worked on ensuring the participation of industrial workers by encouraging equity in the labour market and industrial zones, abolition of Zamindari, Jaigirdari, and Sardari Systems, and exemption of land revenue up to the holding of 25 bighas, i.e., 8.3 acres (Ahmed, M. ‘Bangladesh: Era of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’, University Press Limited, 1983, p. 25).

According to Bangabandhu, these “Measures taken were revolutionary in nature” and he hoped the new policy would go “a long way towards eliminating the perennial conflict that has divided labour and capital” (‘Bangabandhu Speaks: A collection of speeches and statements’, published by the External publicity Division, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh, BGP-71, 72-2787 F-3M). Besides reconstruction and economic development, rehabilitation and restoration were also big challenges for the Mujib government. The Mujib administration undertook a relief and rehabilitation program assisted by the United Nations and reconstituted the Red Cross Society to operate. Relief committees were constituted with five to 10 members at every village, union, thana, sub-division, and district level, with elected representatives, officials, and concerned departments of administration to distribute food and other assistance.

We need to remember that though Bangabandhu faced difficulties in handling the emerging financial and social crises, he was very strong in negotiating foreign loans and grants and always wanted to maintain the dignity of the country. When the World Bank Vice President Mr. Kargill was insisting on sharing the debt burden of united Pakistan, he did not hesitate to say strong words against such a proposal as Bangladesh was not an equal recipient of those loans. The World Bank then had to renegotiate with the Bangladesh team at a much softer term.

Bangabandhu firmly opposed corruption throughout his life. He did not forget to flag this issue even at the very beginning of his administrative journey in independent Bangladesh. Thus, in his speech of 26th March 1972, Bangabandhu said, “Unite. Build fortresses in every house. If you can build such fortresses, 25 to 30 per cent of the woes of the poor and hapless people of Bangladesh would go away. We have so many thieves in our midst! I do not know how these thieves are born. Pakistan has taken away everything from us, but we would have been better off had they taken away these thieves” (Hussain, S. A., ‘Bangabandhu’s Development Philosophy: Reconstruction and Growth with Equity’, Bangabandhu the People’s Hero, External Publicity Wing, MOFA, 2020). His struggle for the reconstruction of Bangladesh’s economy and society was extremely broad-based. And this relentless struggle for an equitable and transparent Bangladesh continued until his last breath.

The author is Bangabandhu Chair Professor, Dhaka University and former Governor, Bangladesh Bank. He can be reached at [email protected]

Leave a Reply